The Future of Organizational Culture

What is Organizational Culture?

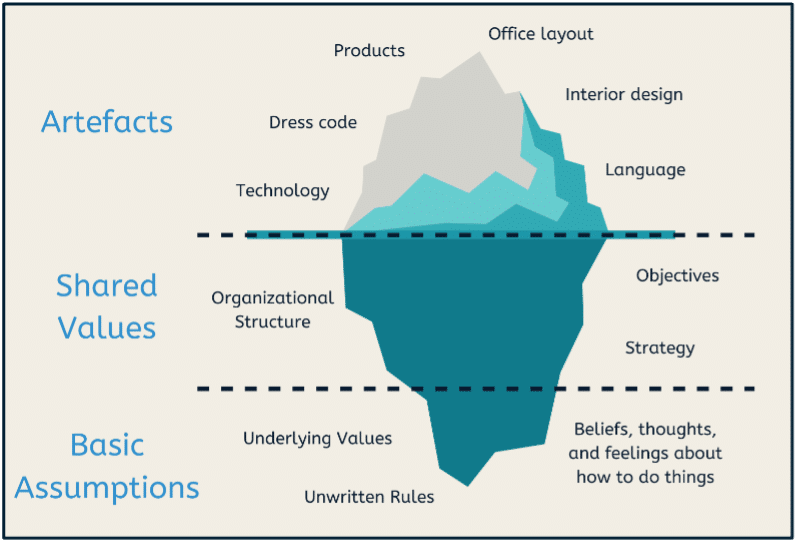

Every organization develops an organizational culture over time as problems are solved and practices are normalized. Culture can be described as the “theme” of the workplace that provides employees with various expectations that guide their thoughts, feelings, and actions (Jex & Britt, 2014). An easy way to understand the elements of organizational culture is through the iceberg metaphor (Sackmann, 1991) based on Schein’s (1990) framework. Above the water, the tip of the iceberg reflects the visible manifestations of culture, or its artefacts, such as the physical office layouts, dress codes, and the language used in an organization (Nanayakkara & Wilkinson, 2021). Just under the water are the shared values of the organization, which can include declared values (explicit values; often seen in places like mission statements) and operational values (used daily to guide behavior, such as organizational structure or meeting expectations; Meissonier et al., 2013). Deeper in the water, the bottom of the iceberg reflects the basic assumptions of the organization, which are unconscious perceptions and beliefs that underlie thoughts, feelings, and actions (Schein, 1990).

Every organization develops an organizational culture over time as problems are solved and practices are normalized. Culture can be described as the “theme” of the workplace that provides employees with various expectations that guide their thoughts, feelings, and actions (Jex & Britt, 2014). An easy way to understand the elements of organizational culture is through the iceberg metaphor (Sackmann, 1991) based on Schein’s (1990) framework. Above the water, the tip of the iceberg reflects the visible manifestations of culture, or its artefacts, such as the physical office layouts, dress codes, and the language used in an organization (Nanayakkara & Wilkinson, 2021). Just under the water are the shared values of the organization, which can include declared values (explicit values; often seen in places like mission statements) and operational values (used daily to guide behavior, such as organizational structure or meeting expectations; Meissonier et al., 2013). Deeper in the water, the bottom of the iceberg reflects the basic assumptions of the organization, which are unconscious perceptions and beliefs that underlie thoughts, feelings, and actions (Schein, 1990).

Why is Organizational Culture Important?

A popular argument for the importance of organizational culture can be reflected in the Attraction-Selection-Attrition Framework (ASA; Schneider, 1987). The ASA framework proposes that culture can be thought of as an organization’s “personality.” Organizations should then desire a clear and cohesive culture so that they attract and select applicants who match its personality. When employees are not a good fit for the culture (i.e., don’t “get along” with it), there may be negative consequences for both the individual (e.g., low morale, withdrawal from work) and the organization (e.g., resources lost in training, high turnover). Culture is not only important for its relation to performance, productivity, and profitability (Kinjerski & Skrypnek, 2006), but also for the guidance and sense of belonging it offers employees.

How is Organizational Culture Shifting?

The increasing popularity of remote and hybrid work has disrupted how culture is developed and maintained. Virtual interactions lack the body language, emotion, and sensations that physical spaces allow, leaving employees feeling disconnected. Workspace layouts, dress codes, and office parties have been limited to small, isolated boxes on a Zoom screen. Employees can no longer “bump into” each other in the office – every interaction is an intentional chat message or call. However, it’s important to realize that these “losses” are all at the tip of the iceberg. While the way that organizational culture manifests itself may look different, the shared values and basic assumptions do not have to—if thoughtful consideration is put toward employee experiences.

Though physical interactions cannot be replicated in a virtual setting, it may not be necessary. While we may feel tempted to revert to traditional artefacts, it’s possible to evolve with the changes the pandemic has prompted. In fact, research has found that physical proximity does not impact employees’ connectedness; however, emotional proximity does. Physical proximity is “being in the same space as another individual—being seen,” while emotional proximity is “being of importance to others—feeling seen” (“Revitalizing Culture,” 2022). Gartner (2022) found that emotional proximity increased employees’ connectedness to their workplace culture by 27%, while physical proximity had no impact. These findings emphasize the importance of facilitating meaningful experiences and bonds between employees without limiting interactions to physical space.

Additionally, we may be past the point of simply going back to the office. Following “Revitalizing Culture” (2022), alignment (that employees know what the culture is and believe that it is right for the firm) and connectedness (they identify with and care about the culture) should be prioritized, rather than preoccupying ourselves with checking all the “right” boxes. Gartner (2022) found that in-office mandates significantly reduced perceptions of connectedness. Specifically, 53% of employees with high autonomy in their job (e.g., freedom with schedule, workload, geographic location) reported high connectedness, while only 18% of those with low autonomy did so. An example of a contributing factor is requiring in-person attendance for meetings when not all employees’ presence is vital. Such mandates can make those employees feel less valued and drive down feelings of connectedness. This low connectedness can further impact the organization more widely, as more connected workers perform at a higher level than less connected workers (by as much as 37%) and are 36% more likely to stay with the organization.

Based on these findings, effort should be put toward fostering a sense of belonging, rather than attempting to mirror “how things used to be”. No amount of water cooler chat alone could convince employees to care about company culture without a deeper sense of connection. Culture is not about the things the office can provide; it’s about how the organization makes people feel. In this way, how culture is described may also need to change. Instead of viewing culture as an impersonable iceberg, a shift toward evaluating culture based on its relationship with our employees may be better advised. While understanding artefacts, shared values, and basic assumptions is theoretically valuable, this framework does not highlight the importance of the people who make up the culture.

How Can You Establish and Maintain an Organizational Culture?

Organizations around the globe are concerned with how to nurture a sense of belonging while being at home. This shared concern led Spotify to survey employees and unpack what belonging means now and in the future (Chamorro-Premuzic & Berg, 2021). The results prompted discussions about what leaders need to keep doing, stop doing, and improve upon to enable a relevant sense of community and culture while people are distributed and in different circumstances. Chamorro-Premuzic and Berg (2021) conclude that leaders today need to:

- Balance culture with diversity and inclusion initiatives

- Have the courage to let culture evolve

- Create social opportunities that really matter to employees whether at home or in an office

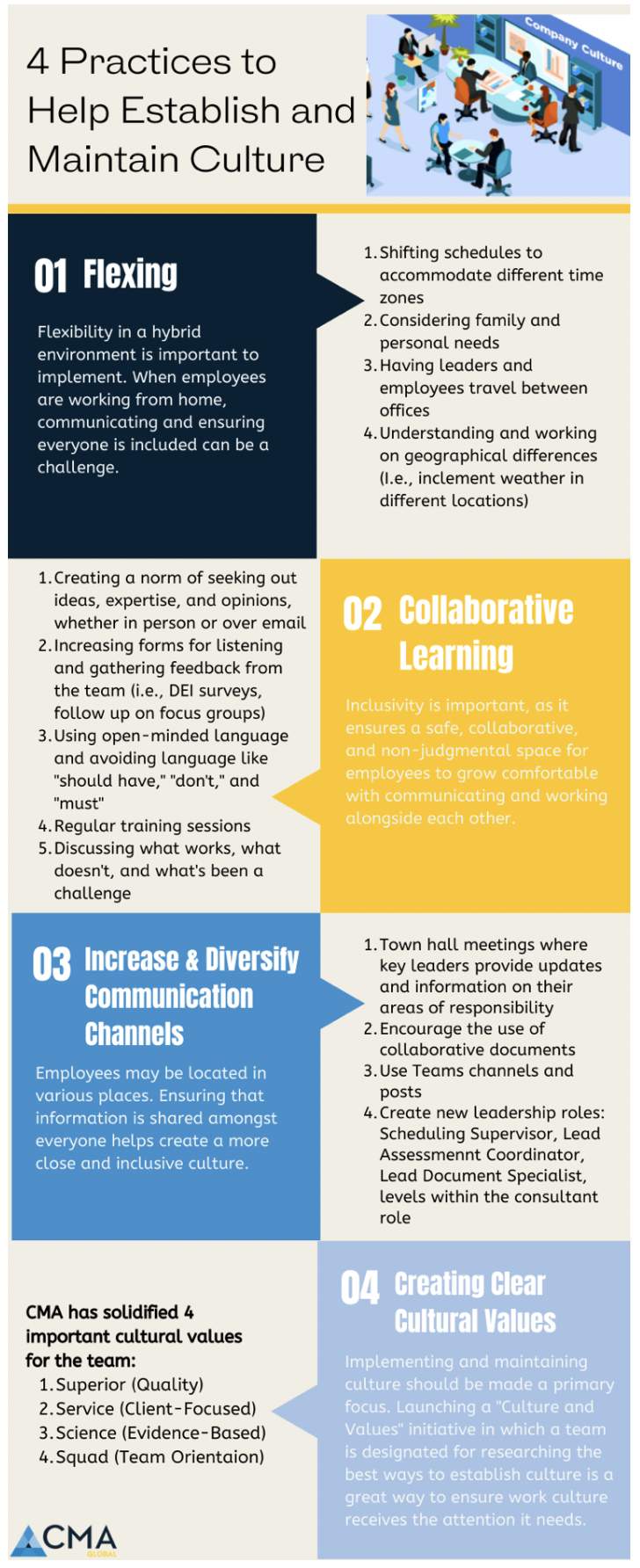

At CMA, we are discovering a new cultural norm. We don’t take our culture for granted and know companies with exceptional cultures must be intentional. CMA has prioritized endorsing culture within the organization to adapt to the new nature of work. Therefore, we would like to share what CMA has implemented to establish and maintain culture in the workplace after the pandemic.

At CMA, we are discovering a new cultural norm. We don’t take our culture for granted and know companies with exceptional cultures must be intentional. CMA has prioritized endorsing culture within the organization to adapt to the new nature of work. Therefore, we would like to share what CMA has implemented to establish and maintain culture in the workplace after the pandemic.

We believe that when your people thrive, your business thrives. We hope you find some of the methods we are using helpful and would love to hear what you are doing to change the culture in your organization.

Company culture is everyone’s responsibility. Covid-19 has upended how leaders interact with employees and how coworkers connect with each other. The need to adapt quickly and remain flexible during the pandemic has also revealed the ineffectiveness of a top-down leadership approach. Culture has become a strategic priority with impact on the bottom line. It can no longer simply be delegated and compartmentalized (Lee Yohn, 2021).

References

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Berg, K. (2021). Fostering a Culture of Belonging in the Hybrid Workplace. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2021/08/fostering-a-culture-of-belonging-in-the-hybrid-workplace

Gartner. (2022). Culture in a Hybrid World [White paper]. Retrieved from https://www.gartner.com/

Jex., S.M., & Britt, T. W. (2008). Organizational Psychology: A Scientist Practitioner Approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kinjerski, V., & Skrypnek, B. J. (2006). Measuring the intangible: Development of the spirit at work scale. In K. Mark Weaver (Ed.), Proceedings of the sixty-fifth annual meeting of the academy of management (pp. 2–16). Retrieved from https://www.kaizensolutions.org/sawscale.pdf

Lee Yohn, Denise. (2021). Company Culture Is Everyone’s Responsibility. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2021/02/company-culture-is-everyones-responsibility

Meissonier, R., Houzé, E., & Bessière, V. (2013). Cross-cultural frictions in information system management: Research perspectives on ERP implementation misfits in Thailand. International Business Research, 6(2), 150–159. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.989.7110& rep=rep1&type=pdf

Nanayakkara, K., & Wilkinson, S. (2021). Organisational culture theories: Dimensions of organisational culture and office layouts. In R. Appel-Meulenbroek, & V. Danivska (Eds.), A handbook of theories on designing alignment between people and the office environment (pp. 132-147, 294 Pages). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. doi:10.1201/9781003128830-12

Revitalizing Culture in the World of Hybrid Work (2022). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2022/11/revitalizing-culture-in-the-world-of-hybrid-work

Sackmann, S. A. (1991). Uncovering culture in organizations. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 295–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886391273005

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. The American Psychologist, 45(2), 109-119.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel psychology, 40(3), 437-453.