When Trust is Broken: What it Means and How to Repair it

Trust and Trust Repair

Trust is fundamental in any relationship. We can feel when we are trusted and understand when we have lost trust; yet, we often have difficulty describing exactly what it is. Researchers most frequently define trust as the willingness of a person to be vulnerable to another based on the confident expectations that they will act in beneficial ways (Mayer et al., 1995). In simple terms, trust means believing that you can rely on someone to help you. Unfortunately, trust is fragile. One misstep can harm a relationship beyond repair if not properly addressed. Therefore, it’s important to understand what it means to break trust and how to properly repair it.

When trust is breached, the damage can be extensive. The repercussions may extend beyond cooperation on a professional level, leading to a fundamental distrust of one’s values and intentions. The range of reactions may be best understood through the nature of the violation. There are two types of trust violations: competence and integrity. Competence violations occur when someone fails to meet expectations involving technical and interpersonal skills required for successful performance (McAllister, 1995). This can generally be seen as a mistake, such as accidentally giving someone the wrong information. On the other hand, integrity violations occur when someone acts in an unethical manner or breaks a promise (McAllister, 1995). Integrity violations themselves are intentional, whether the impact on others is intentional. For example, someone may decide to lie about a deadline to ensure it gets done on time. While they may think they are doing something good, the person they lied to may feel betrayed when they find out. Integrity violations are seen as more severe and are more difficult to repair, as people may attribute the violation to one’s identity, rather than the situation at hand. Understanding how the violation is perceived (i.e., as a competence or integrity violation) is vital to repairing trust, as different strategies must be used, and different aspects must be addressed.

Before moving on to the strategies to rebuild trust, it should be noted that not all trust can be repaired and repaired trust may never be the same as pristine trust. Whether or not you achieve forgiveness, the important thing is that you are moving forward with authenticity and sincerity.

Trust Repair Tactics

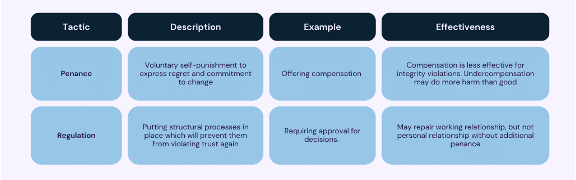

There are several tactics to trust repair which can broadly fit into two categories: substantive and non-substantive. Substantive trust repair strategies include concrete actions with tangible elements that are meant to restore balance by addressing the negative social exchange itself (Dirks, 2011). Below are summaries of the two most common substantive tactics.

While these tactics are generally effective, they may be more relevant to forgiveness than reconciliation, meaning that an individual may be willing to continue to work with the other, but the personal relationship will not be restored (DiFonzo et al., 2020). Neither tactic truly addresses the harm done to the trusting relationship, but rather attempts to “even the score”.

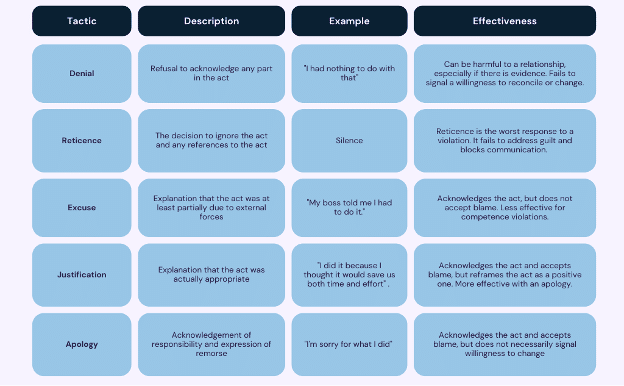

Non-substantive repair strategies describe tactics for trust repair which have purely verbal components and are meant to re-cast negative perceptions (Dirks, 2011). Below are summaries of common non-substantive repair strategies.

Because all these strategies are strictly verbal, they require one’s word to be taken at face value. If this is the first time you’ve broken their trust in a longstanding relationship, this may be a possibility. However, if you’ve broken their trust before or if you haven’t known each other for very long, this may not be enough to show that the violation of trust does not reflect your true intentions. Does this then mean that there is no way to repair trust? Fortunately, it doesn’t. As you may have guessed, it’s possible to combine tactics to express a genuine desire to rebuild both the working and personal relationships. This combination of tactics is seen in the substantive apology.

The Substantive Apology

An apology can be more than just saying “I’m sorry”. When done right, it can instill confidence and inspire reconciliation. The most important aspect of repairing a trusting relationship is being sincere (Lewicki & Bunker, 1996), as it is essential for building and sustaining lasting relationships. If you are unwilling to truly reconcile, you should not use this strategy. Instead, you should be transparent and communicate your intentions, using substantive strategies to negotiate an effective way to continue to work together. If you are genuine in your desire to mend fences, then learning how to apologize effectively will be invaluable.

Researchers have extensively studied the science of the apology, coming to several general conclusions:

- Apologies should be given as soon as possible after the transgression. A prompt apology conveys concern about the impact (Kähkönen et al., 2021).

- Apologies are more effective for competence than integrity violations (Kim et al., 2004; Lewicki et al., 2016). Further, as perceived intentionality increases, restorative actions are less effective for forgiveness (Martinez-Diez et al., 2021).

- Apologies may be seen as insincere if there are frequent transgressions (Lewicki & Brinsfield, 2017), if the apology is not detailed (Shapiro et al., 1994), or if they do not perceive the transgressor as remorseful (Tomlinson et al., 2004).

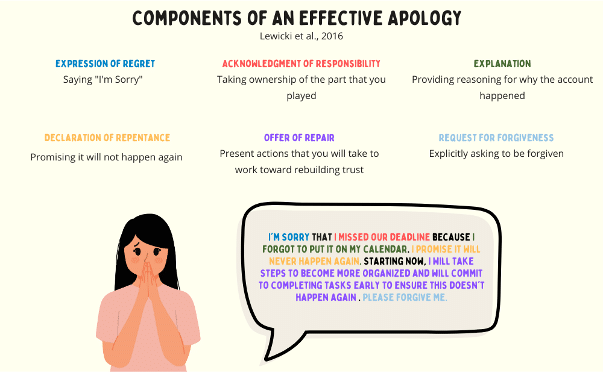

Additionally, Lewicki et al. (2016) has gone so far as to identify the ingredients to an effective apology:

While the components have an additive effect on forgiveness (i.e., more components = more effective; Lewicki & Brinsfield, 2017), not all components are needed for every situation, and not all of them are equally useful. The most critical components for an effective apology are acknowledgment of responsibility, explanation, and offer of repair (Lewicki and Polin, 2012), as they signal a commitment to making things right. Whether you follow the exact formula or not, it is paramount that you follow through with your words and make doing so a priority. Promises only go so far and failure to commit to reconciliation can quickly deteriorate the relationship more than if you had never apologized at all.

Ultimately, even if you do everything you can to rebuild trust, it’s up to the other person to forgive you. If they decide not to accept your apology, you must respect their decision. However, this does not stop you from following through on your actions to repair the relationship, where possible. Even if they choose not to continue working with you, you should use the experience as a learning opportunity and apply what you have learned to future relationships.

References

DiFonzo, N., Alongi, A., & Wiele, P. (2020). Apology, restitution, and forgiveness after psychological contract breach. Journal of business ethics, 161(1), 53-69.

Dirks, K. T., Kim, P. H., Ferrin, D. L., & Cooper, C. D. (2011). Understanding the effects of substantive responses on trust following a transgression. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114(2), 87-103. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.10.003

Kähkönen, T., Blomqvist, K., Gillespie, N., & Vanhala, M. (2021). Employee trust repair: A systematic review of 20 years of empirical research and future research directions. Journal of Business Research, 130, 98-109. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.019

Kim, P. H., Ferrin, D. L., Cooper, C. D., & Dirks, K. T. (2004). Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for repairing competence- versus integrity-based trust violations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 104-118. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.104

Lewicki, R. J., & Brinsfield, C. (2017). Trust repair. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 287-313. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113147

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research, 114, 139.

Lewicki, R. J., & Polin, B. (2012). In Kramer R. M., Pittinsky T. L. (Eds.), The art of the apology: The structure and effectiveness of apologies in trust repair. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lewicki, R. J., Polin, B., & Lount, R. B., Jr. (2016). An exploration of the structure of effective apologies. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(2), 177-196. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1111/ncmr.12073

Martinez-Diaz, P., Caperos, J. M., Prieto-Ursúa, M., Gismero-González, E., Cagigal, V., & Carrasco, M. J. (2021). Victim’s perspective of forgiveness seeking behaviors after transgressions. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 1161.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.2307/258792

McAllister, D. J. 1995. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38. 24-59.

Shapiro, D. L., Buttner, E. H., & Barry, B. (1994). Explanations: What factors enhance their perceived adequacy? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58(3), 346-368. doi:https://doi-org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1006/obhd.1994.1041

Tomlinson, E. C., Dineen, B. R., & Lewicki, R. J. (2004). The road to reconciliation: Antecedents of victim willingness to reconcile following a broken promise. Journal of Management, 30(2), 165-187. doi:http://dx.doi.org.portal.lib.fit.edu/10.1016/j.jm.2003.01.003